In a previous post, we saw how Beijing was already exploring the idea of military intervention in Siberia in February 1918. The Duan government went so far as to sign a Joint Military Defence Agreement with Japan in May, with an eye to “defensive action” against the influence of the Central Powers in Russia. As long as Allied opinion remained divided, however, actual deployment proved elusive. Washington was concerned about the impact on Russian public opinion, as well as the potential for expanding Japan’s influence in Northeast Asia. The Japanese government was split between hawks and doves, with the former kept restrained by America’s lukewarm attitude.

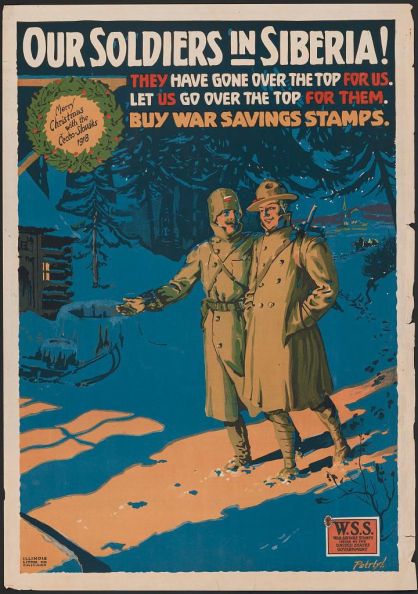

The Czechoslovak Legion’s revolt in summer 1918 broke the deadlock. In America, military intervention could now be sold as assistance to the embattled Legion, fighting heroically against German and Austrian POWs. On 6 July, Washington decided in favour of intervention. This gave the Japanese hawks the ammunition they needed and, on 16 July, the Advisory Council for Foreign Affairs (Gaiko Chosakai) approved a draft calling for the deployment of an unrestricted number of troops to Siberia.

Even before this, however, the Japanese military began increasing its support for anti-bolshevik forces. Military advisors had been dispatched to both Semenov and Horvath since the beginning of 1918. Now a steady stream of soldiers began trickling towards the front, much to the alarm of Chinese officials.

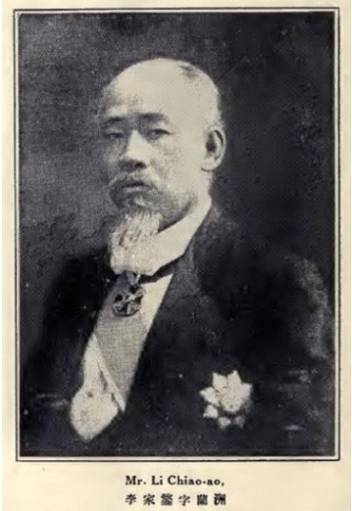

協約各國共同出兵問題,已有動機,不久必見諸事實等情,曾於有日電呈在案,已邀鈞鑒。頃據確實探報,近有日本兵士,俱著便服,或一、二百,或三、五百名不等,由南滿、中東兩路陸續至海參崴、哈爾濱、滿洲裡等處。雖未持有槍械,而隨行車上,各載有木箱若干,內裝何物,不許他人過問,復不受檢查,其為暗運槍彈,不問可知。此項兵士,系該國之義勇隊與退伍之陸軍,便裝出發,分布崴、哈等處,並不頒布動員令,以防各國之詰責。其用意至深,其居心叵測。從各方面探得確實消息,征以本署顧問齊藤中佐之言,大約以義勇隊赴滿助謝,以退伍之陸軍為共同出兵之前驅。一俟協約國實行出兵時,彼即改易軍服,集而成軍等情。謹電馳聞。伏乞垂鑒。

On the issue of joint Allied intervention, there have been some developments and we will soon see the truth of the matter. I had previously wired about this on the 25th for your perusal. Now, according to accurate reports, there have recently been Japanese soldiers dressed in civilian uniforms, in groups of 100-200 or 300-500, travelling in succession via the South Manchurian and Chinese Eastern Railways to Vladivostok, Harbin and Manzhouli. Although they are not bearing arms, they are accompanied by trains each carrying several wooden crates. As for what these contain, they do not permit others to enquire and will not submit to checks. That they are being used to secretly transport weapons need not even be asked. These soldiers are volunteers and demobilised infantrymen of that country, leaving in civilian clothes and stationed in Vladivostok, Harbin etc. Moreover, no mobilisation order has been announced in order to forestall questions from other countries. Their intentions are extremely obscure and it is hard to guess at their purposes. Based on accurate information obtained from various sources, an enquiry was made with Colonel Saito – an advisor with my office – who said it is likely that the volunteers are going to Manzhouli to aid Semenov and the demobilised infantry will be frontline troops for the joint intervention. Once the Allies carry out the intervention, they will immediately switch to military uniform and assemble as a force. For your kind consideration.

Telegram from Meng Enyuan, 28 July 1918. Zhong-e guanxi shiliao, Minguo jiunian zhi banian (1917-1919): chubing Xiboliya, p. 224.

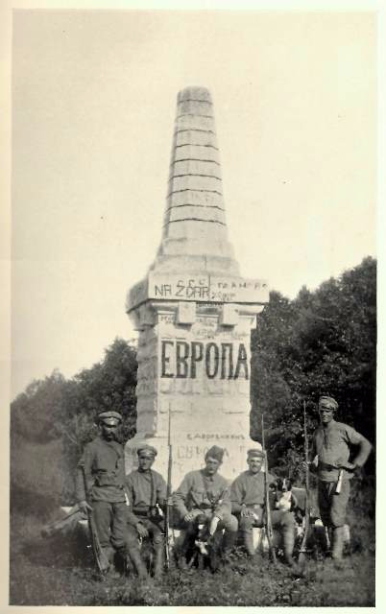

Semenov had been under pressure from the Reds at Manzhouli since June, and some of the soldiers mentioned in Meng’s telegram were indeed members of a 500-strong volunteer battalion – organised by Major-General Muto Nobuyoshi – sent to rescue him. In April, the Japanese had also landed several hundred troops from their warships in Vladivostok, providing cover for the demobilised soldiers. But whatever the exact number or destination of these forces, they were a sign of the Imperial Japanese Army’s broad scope of action in Manchuria and the Russian Far East. Already in February, Vice-Chief of Staff Tanaka Giichi, one of the foremost advocates of unilateral intervention, had set up a secret Military Affairs Cooperative Committee to prepare for full-scale operations in Siberia. And even as the Terauchi government and the popular press debated the desirability of intervention, the army general staff had a free hand in sponsoring anti-bolshevik clients and mobilising emigre volunteers.

More galling for Meng – in spite of his own entanglements with Japanese advisors – was China’s inability to do anything about these troop movements. The Joint Defence Agreement expressly permitted the Japanese army to use the CER for military purposes, as long as it did not contravene the original Sino-Russian railway treaties. This was the first inkling that Duan Qirui’s appeasement of the Japanese would have dire consequences for China’s authority over the Railway zone.

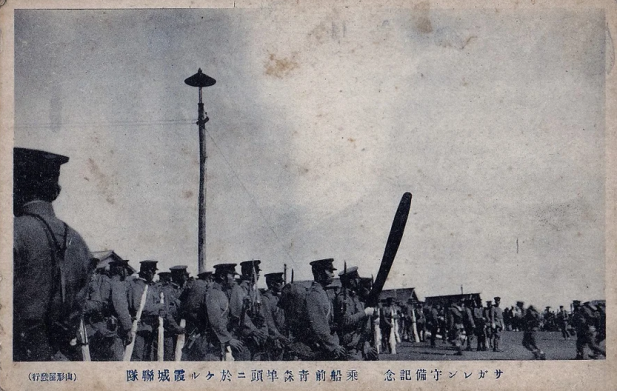

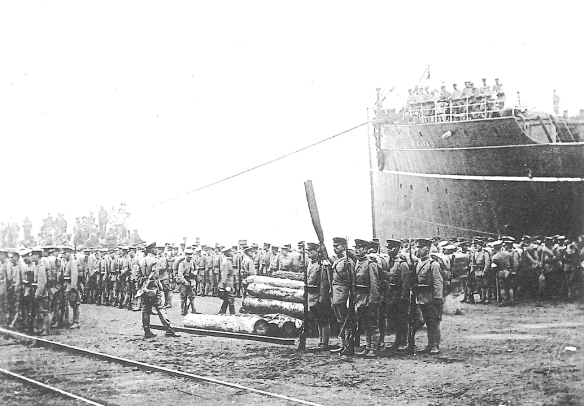

On 2 August, after an exchange of notes with the Americans, the Japanese government officially announced its intention to send its forces to Vladivostok. This was framed as a response to German and POW activity in Russia and a defence against “chaos”. What was missing, however, was a firm commitment to the American proviso that the number of troops be limited to 7,000. Instead, the Japanese reserved the right to send reinforcements if necessary, following consultation with the Allies. Troops could also be deployed in areas other than Vladivostok.

With the brakes now taken off the Imperial Japanese Army, there was no more need for subterfuge. The first elements of the 12th Division left Kokura for Vladivostok on 10 August; one day after they landed, the division commander requested immediate reinforcements. The Japanese government then agreed that the 7th Division, stationed along the South Manchurian Railway, would be sent to bolster Semenov in Manzhouli, directly contravening the original declaration but permissible under the Sino-Japanese Joint Defence Agreement. These were followed by yet further reinforcements from South Manchuria called up by the general staff, asserting its “right of supreme command” in the battlefield without consulting civilian politicians. Just three weeks after the Japanese announcement, the stage was set for large-scale military operations across East Siberia and the Russian Far East.