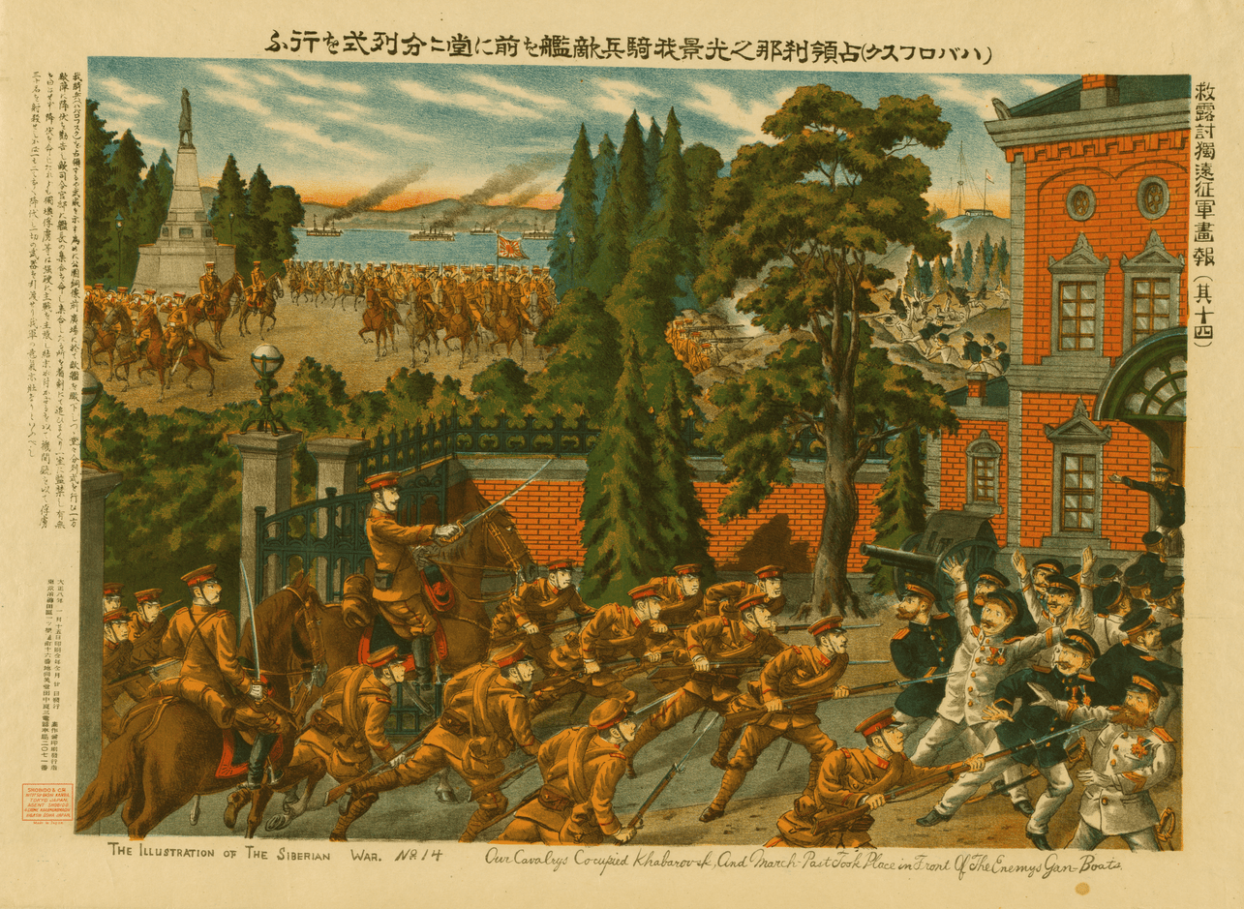

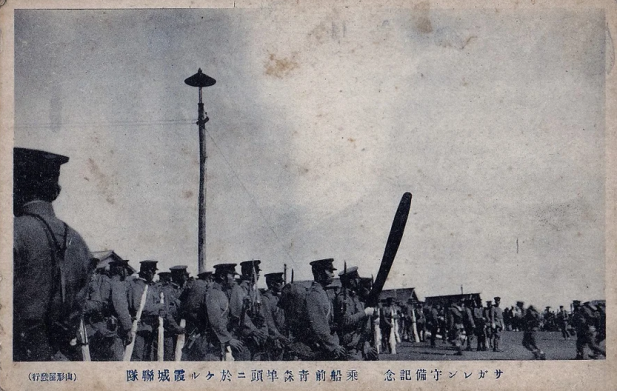

The stretch of the Amur River around Blagoveshchensk had been one of the Reds’ last holdouts. When White and Japanese forces captured the city in September 1918, they put an end to six months of Soviet rule that had devastated a once-bustling provincial capital. Ataman I.M. Gamov, who had fled to China in March 1918 after a failed uprising against the Soviets, returned to Blagoveshchensk triumphant. Yet the Amur region soon became a hotbed of partisan activity. Bloody attacks against the Whites and the Japanese escalated throughout the early months of 1919, with the involvement of seasoned Bolshevik F.N. Mukhin. These were met with punitive detachments that arbitrarily executed suspected Reds, further antagonising the local population.

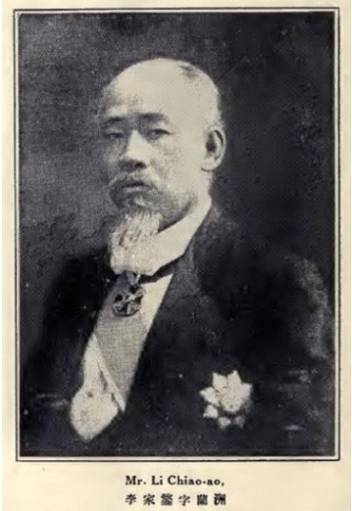

Chinese officials watched the cycle of violence from across the Amur with increasing concern. Already in early February, Heihe circuit intendant He Shouren spoke of Japanese and White atrocities in Il’inovka; the villagers appealed to the Chinese for help and resolved to resist further raids with violence. The situation had deteriorated so severely by the middle of the month that Heilongjiang military governor Bao Guiqing sounded a note of alarm.

前接黑河巴司令文電稱:

「接日本副領事阪東通告,奇克特太平溝對岸俄境,集有激黨四百余名,駐伯力日軍高橋聯隊長已在俄岸擦比塔了南方一百八十裡地點交兵。駐河日軍於冬日赴俄境諾肯齊下游米海諾夫辨卡亞地方迎頭堵擊等語。除派隊馳往奇克特、烏雲、寶興一帶會同各防嚴加堵御,並授以機宜,如激黨潰散我岸,能相機解除武裝送部處置更善,倘敢反抗,即行攻擊外,應請電飭第二混成團駐蘿北各防一律堵截」等情。

當經電復,並飭駐蘿防軍嚴行防堵,勿令竄入,如激黨潰散我岸,應即解除武裝,倘敢反抗,即以武力對待去后。茲復接巴司令、何道尹寒電稱:

「昨派翻譯譚咸慶過江,調查起事原因,並証以各方面所聞,大概前政黨敗避我岸,圖謀恢復,時勾結各屯響應,各屯以既在激黨勢力范圍,未敢輕舉,因之飲恨。及政黨克復阿省,不思收拾人心,反借日軍勢力,輒指為亂黨,肆行殺掠,激成公憤,殘余亂黨從而煽惑,遂致於此,並有十七屯民變之風傳。今午司令晤俄領,亦以阿省軍隊附和日軍,辦理不善為恨事。正擬會報間,適阿省華僑報稱,阿省全境過激派頗有死灰復燃之勢,現在已有動機,昨晚阿城險象岌岌,兵營乘機縱火,日軍與舊黨嚴為戒備,幸免其禍,已飭各團營嚴密戒備」等語。

除電復並分飭沿邊軍隊加意防范,隨時探報暨分電外,謹聞。

A wire was received from Heihe commander Ba [Ying’e] on 12 February, saying:

‘According to a notice from Japanese vice-consul Bando, more than 400 Reds have gathered on the Russian side of the river opposite Qikete [today Qike zhen] and Taipinggou. Regimental commander Takahashi of the Japanese troops stationed in Khabarovsk has already fought them at a location 180 li south of Cabitale[?] on the Russian bank. The Japanese troops at Heihe left for Mikhailovka, downriver from Innokent’evka, on 2 February to head them off. I have rapidly deployed troops to the Qikete, Wuyun and Baoxing area to shore up defences together with the border guards. Guidelines have also been issued that, if the Reds are defeated and flee towards our bank, it would be best if they could be disarmed and sent to the headquarters to be dealt with. If they dare to resist, they should be immediately attacked. At the same time, I request that the sentries of the 2nd Mixed Regiment in Luobei be instructed to block them off as well.’

I wired a reply and instructed the Luobei sentries to be on strict guard and block [the Reds], not allowing any of them to slip in. If the Reds are defeated and flee towards our bank, they should be immediately disarmed. If they dare to resist, they should be dealt with immediately by force of arms. Now a wire of 14 February has been received from commander Ba and circuit intendant He, which said:

‘Yesterday, translator Tan Xianqing was dispatched across the river to investigate the causes of the unrest. Based on what was heard from various sources, it seems that when the former governing party was defeated and fled to our bank, they planned a revival and frequently colluded with several villages to rise up in support. Since the villages were within the Red sphere of influence, they did not dare to act rashly. Hence [the party] nursed a grievance against them. When the governing party returned to Amur oblast’, they did not think of winning over the people, instead relying on the power of the Japanese army. They arbitrarily accused people of being Reds, murdering and looting at will and inciting popular anger. The remaining Reds could then agitate among them, which has led to this. There is also a rumour of a popular uprising in 17 villages. This afternoon, the commander [Ba] met with the Russian consul and said it was regrettable that the troops in Amur oblast’ were in league with the Japanese and had managed things poorly. Just as we were about to make this report, Chinese migrants in Amur oblast’ reported that the Reds in the whole of the province were showing strong signs of a resurgence and have already begun to act. Last night, Blagoveshchensk was in a state of alarm and soldiers in the barracks took the opportunity to commit arson. Japanese troops and the Whites were on high alert and thankfully a disaster was avoided. The various units have been instructed to be on strict guard.’

I have wired a response and instructed border troops to pay close attention to defence, as well as report on information gathered.

Telegram from Bao Guiqing, 22 February 1919 (sent 16 February), in Yujun Wang, Tingyi Guo and Qiuyuan Hu (eds.) Zhong-E Guanxi Shiliao: E Zhengbian yu Yiban Jiaoshe (2), Minguo Liunian zhi Banian (Taipei: Zhongyang Yanjiuyuan Jindaishi Yanjiusuo, 1960), p. 64.

Bao’s report highlighted how White misgovernment and the behaviour of the Japanese army had so alienated the population that the countryside was on the brink of revolt. Of particular note, however, is that Chinese concerns about the partisan movement centred on mobile populations. The growing violence in Amur oblast’ would send refugees and Reds fleeing into China, just as Gamov and the Whites had. It also directly threatened the region’s sizeable Chinese diaspora. This latter point was emphasised by the migrants’ own advocacy, channelled through the newly-formed Amur Oblast’ Diaspora Association.

續據黑河巧、效電稱,伊萬諾夫屯聚黨萬余,條晚與舊黨及日軍劇戰,雙方傷亡六七十人,又過激黨勝利,日軍傷亡百余,陣亡堀大隊長一員,鄉民愈聚愈眾,阿省可危。並據華僑總會報稱,該屯華僑分會長會員均退回阿,惟僑民及財產甚多,無法搬運,已請俄省長及日領知照前敵保護。又稱黑河逼近俄岸,如難民來黑,如何應付,乞示機宜等情。

查俄民逃來避難,恐夾有激黨,致俄舊黨及日軍借端搜索,轉為主權邊境有妨,當飭設法阻止。除電復辦外,是否有當,仍乞查照號電各節,一並核示飭遵為盼。

Further telegrams of 18 and 19 February from Heihe state that more than 10,000 Reds have gathered in Ivanovka village. On the night of the 17th, they did battle with the Whites and Japanese troops, 60-70 were killed or wounded on both sides. The Reds were victorious, more than 100 Japanese soldiers were killed or wounded. Battalion commander Hori was killed in action. The villagers are gathering in ever greater numbers and Amur oblast’ is in danger. Also, according to a report from the Chinese diaspora association, the leader and members of its branch in that village have all retreated to Blagoveshchensk. However, the migrants and their property are very numerous there and they cannot move. The Russian governor and Japanese consul have been requested to inform the [troops at the] front to protect them. The report also said that Heihe is close to the Russian bank and asked for guidelines on what to do if refugees arrived.

If Russians flee here to escape the disorder, I fear that there may be Reds among them, which would give the Whites and Japanese troops a pretext to conduct searches. This would then undermine sovereignty and the border situation. I have instructed that they should be stopped. A response has been wired to implement this. As for whether this is appropriate, I earnestly seek your instructions on the matter together with the various items in the telegram of the 20th.

Telegram from Bao Guiqing, 22 February 1919 (sent 21 February). Ibid., pp. 64-65.

Chinese border officials thus recommended the same approach towards all escapee Russians, be they Reds or Whites. Both were threats to border security. They should be prevented from entering Chinese territory or, failing which, should be disarmed beforehand. Where the Whites differed from the Reds was in their treatment of the Chinese diaspora and their collusion with the Japanese army. Bao was already well aware of the mistreatment of Chinese migrants by Semenov; now it seemed that the Whites in Amur oblast’ were just as ruthless.

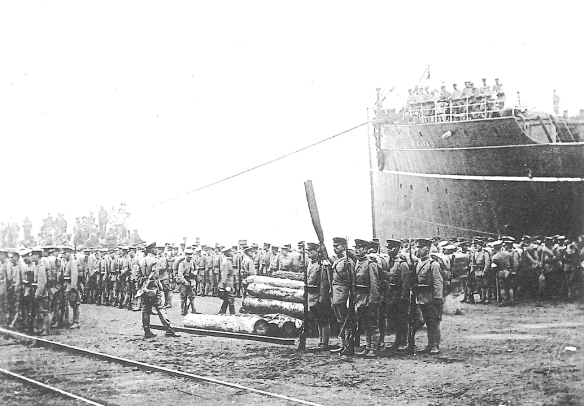

The disturbances along the Amur culminated in the Ivanovka Incident of 22 March, when White and Japanese forces decimated the village following an abortive partisan attack on Blagoveshchensk. Just as the diaspora association had warned, several Chinese were among the 257 casualties. This cemented the Whites’ reputation for anti-Chinese brutality at a time when the Red Terror and War Communism had not yet made inroads into the Russian Far East. Although the Reds were ideological extremists and harbingers of revolution, the Whites now seemed no better. The Whites’ callousness antagonised Russian villagers and Chinese officials alike – a mistake that would haunt them as the movement collapsed in winter 1919.