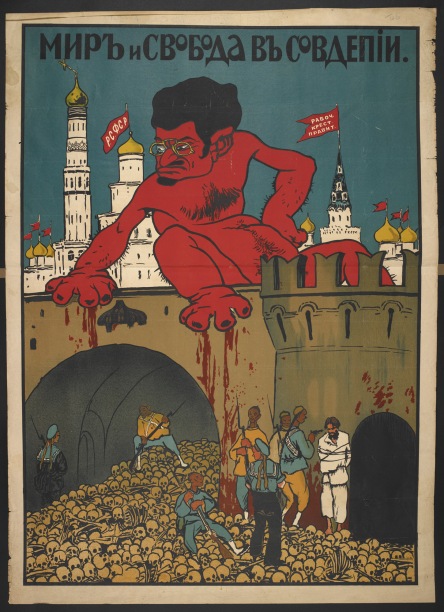

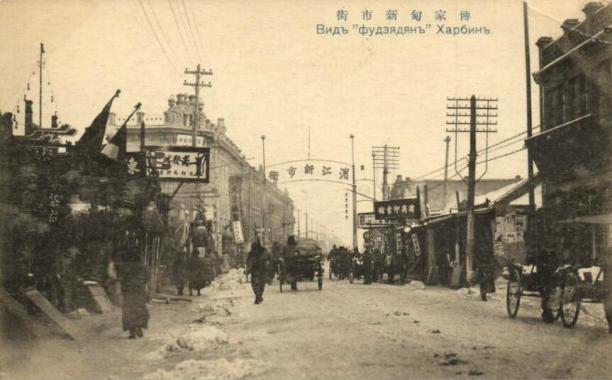

In January 1918, following the Bolshevik seizure of power, the Beijing government placed an embargo on Manchurian exports to Siberia. Consular certification was necessary to send goods, including basic foodstuffs, to Vladivostok and Irkutsk. This revealed some cracks in Allied policy: Britain and France had insisted on the embargo, Russian ambassador Kudashev disapproved, and the American government feared that it would alienate ordinary Russians.

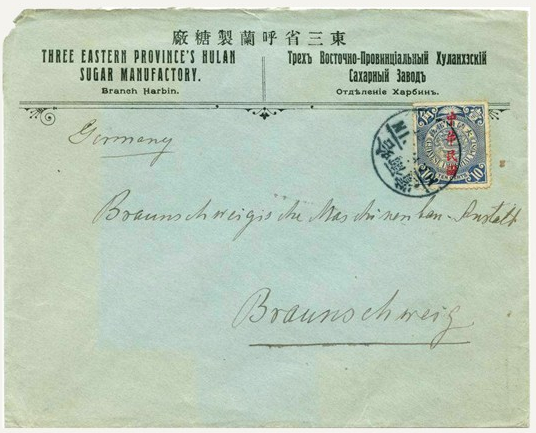

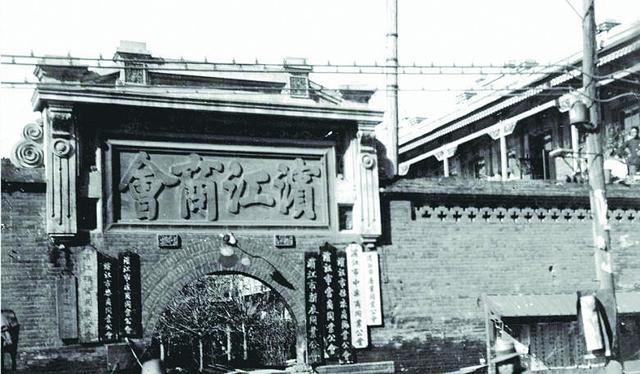

Given the extensive trade links between China and Russia, it was natural that Chinese merchants would also suffer as a result. While America petitioned the other Allied powers to lift the embargo throughout the spring, Chinese firms wrote their own protests. A joint letter from Dong He Hong and 23 other Harbin grain firms provides an insight into the volume of trade, prices, and the types of argument used in support of the merchants’ position.

竊查哈爾濱開埠二十年,市面發展,幾與津、滬並稱,實以糧商為中堅。糧商之業務,營運小麥、元豆,專恃出口為大宗,元豆行銷於東西各國,常年輸出額可達三千萬普特(每普特合華秤三十觔),小麥行銷俄國境內,常年輸出額可達一千萬普特,輸出愈繁,獲利愈鉅,市面之發展亦愈速,此其大較也。自歐戰發生,元豆輸出額頓減數量,商等已顯受影響,然尚可營運小麥,行銷俄境以內,故糧商雖困,尚未至於大困。近因俄國軍工黨蠢蠢肆擾,外交團要求政府並小麥亦禁止出口,糧價遂一落千丈。客冬商等買存糧石,小麥每普特計合羌洋十二元,元豆每普特計合羌洋八元,今春小麥價值每普特僅合羌洋三元有奇,元豆每普特僅合羌洋二元有奇,其實空懸行市,並無實存之戶,將來之跌落,仍無限度。就商等現狀言之,已皆虧累不堪,倘糧價再跌,勢必全體倒閉,債務相關,彼此牽連,恐其他商戶亦不能支矣。商等切膚之患,即哈埠市面盛衰關鍵,擬懇恩予轉詳,特弛小麥出口之禁,不惟商等死灰復燃,即市面亦蒙無疆之庥。

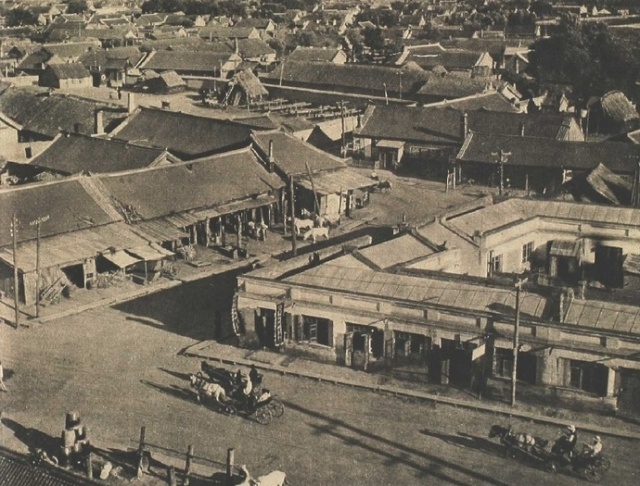

The port city of Harbin has been established for 20 years; the development of its markets can almost be mentioned in the same breath as Tianjin and Shanghai, with the grain trade at its core. The business of grain merchants involves trading in wheat and soybeans, with reliance chiefly on exports. Soybeans are sold in both eastern and western countries, and in an average year exports can each 30 million pud (each pud equivalent to 30 Chinese jin). The wheat is sold in Russian territory, with average annual exports reaching 10 million pud. The more exports there are, the higher the profit and the more rapidly the market develops; such is the situation in general. Since the European War occurred, the tonnage of soybean exports has fallen and we have clearly been affected. However, it was still possible to deal in wheat, to be sold in Russian territory. Hence, although the grain merchants were troubled, this did not reach the level of great distress.

Recently, because the Russian workers’ and soldiers’ faction was provoking unrest, the diplomatic corps asked the government to restrict exports of wheat as well and its price has then fallen precipitously. Last winter, we bought and stockpiled grain, with wheat at 12 rubles and soybean at 8 rubles per pud. This spring the price of wheat is only a little more than 3 rubles, and soybeans a little more than 2 rubles per pud. In fact these are only abstract quotes, without any real sales, and future depreciation will be limitless. Speaking of our current situation alone, we are all experiencing intolerable losses. If grain prices were to fall again, it would lead to wholesale collapse and, with the issue of debt involved, one fears that other merchants would also not be able to maintain themselves. The imminent peril we face will determine whether the Harbin market thrives or declines. We earnestly ask that you look favourably on our report and lift the embargo on wheat exports in particular. Not only will we have a new lease on life, the market too will obtain immeasurable relief.

The petition thus begins with no small measure of alarmism and reiterates the importance of the merchants’ success to that of the city as a whole. It then goes further to emphasise the benefits of trade for the treasury as well as for the people at large.

況穀賤傷農,故有名言,若糧食得以出口,價值必漸升騰,鄉屯墾戶,利賴亦多。且糧石由玻璃、黑河等地出口者,概由江船裝運,按江關稅則,每小麥一百斤抽收稅銀六分六厘六毫六絲,每普特計重三十斤,若出口有一千萬普特之小麥,計重三萬萬斤,通盤合算,可增收稅銀二十二萬二千一百九十餘兩。縱由火車分運半數,然江船裝運,尚有五百萬普特,亦總可增收稅銀一十一萬一千零九十餘兩,實於鈞關收入,大有補助。或者疑為小麥出口,如北滿民食何。或者又疑俄國軍工黨多係親德派,若小麥出口,未必不轉濟德國民食,如齎盜糧何。商等謹證之事實,以釋此疑。查北滿一代,居民樸素,專食紅糧、小米、包米等糧,凡一切冠婚喪祭及購置農具,全恃糶賣豆麥,以供需用,今弛出口之禁,不惟無礙民食,且於農家日用,多所活動。

After all, low grain prices harm farmers – this is a well-known saying. If grain can be exported, its price will gradually rise and the villages and farms will have more to depend on. Moreover, the grain exported from Khabarovsk and Heihe is all transported by ship. Going by the river customs duties, 0.06666 yuan is levied on each 100 jin of wheat. Each pud is 30 jin. If 10 million pud of wheat is exported, equivalent to 300 million jin, a total of more than 222,190 liang in duties may be levied. Even if half were exported by rail, a remaining 5 million pud would still be transported by ship, and a total of more than 111,090 liang in duties may be levied. It would indeed be a great boost to the income of your customs.

One may wonder: If wheat were exported, what would the people of North Manchuria eat? Or one may suspect that most of the Russian workers’ and soldiers’ party are pro-German and, if wheat were exported, would it not be used to supply the German people, like feeding thieves? We carefully consider the facts in order to address these queries. In the North Manchurian region, the people are simple and mainly eat grains such as sorghum, millet and maize. The conduct of coming-of-age ceremonies, weddings, funerals and sacrifices, as well as purchasing of farm equipment, are entirely dependent on the sale of soybean and wheat to meet their needs. By lifting the embargo now, not only would the people’s food supply be unaffected, it would also greatly support the farmers’ daily expenses.

The merchants then conclude with an argument not unlike that of the Americans’, that supplying the Russians would generate goodwill and draw support away from the Bolsheviks.

人之恆情,大抵為人之心,不敵其救死之心,向來北滿小麥輸入俄境,僅敷該國民食之用,無再轉輸他國之餘裕,矧俄國大兵之際,連年荒旱,凡軍工黨之份子,其反對政府者,不過十之一二,其迫於飢寒者,實占十之八九,今弛小麥出口之禁,俄民飢而遇食,救死不瞻,更何能接濟他國。且飲食粗足,一般窮極思亂之軍工黨,或可稍為息心。果爾,則吾國邊防,不至吃緊,俄國內亂,亦可減輕,此等利益,當亦為俄國舊政府所承認。總之,小麥出口,非惟惠商,且可利農,非惟增收稅入,亦可藉弭邊患。而揆諸救災恤鄰之道,更屬仁至義盡,一舉數善,何憚不為。商等不揣冒昧,為此呈請鈞署轉詳財政部,提交國務會議,向外交團交涉,仍許西比利亞鐵路並黑河、玻璃等處運輸小麥出口,以恤商艱,而集眾益,不勝感激待命之至。

It is a common sentiment, in general, for one’s own self-interest to be superceded by the desire to save others. All along, the export of wheat from North Manchuria to Russia has been sufficient only for the needs of the Russian people, with no surplus that can be transferred to another country. And now Russia is at war, with successive years of drought and famine. Of the members of the workers’ and soldiers’ party, those who oppose the government make up one or two out of ten; those forced to do so by cold and hunger in fact make up eight or nine out of ten. If the wheat embargo is lifted now, the hungry Russian people will have food. It may not even be sufficient to save them, so how can they relieve another country? Moreover, with sufficient food and drink, the workers’ and soldiers’ party – which always hungers after disorder – may be diminished somewhat. If so, our country’s border defences will not come under threat and Russia’s internal troubles may also lessen. Such benefits would naturally be acknowledged by the former Russian government as well.

In sum, the export of wheat will not only favour the merchants, but also benefit the farmers; not only increase tax income, but also resolve border troubles. And exercising the principle of saving a neighbour from catastrophe – that would be the utmost expression of kindness. One act alone would bring many virtues, why fear a bad outcome? We presume to ask your office to convey this to the Finance Ministry and bring it before the State Council for discussion and negotiation with the diplomatic corps, that export shipments of wheat via the Siberian railway, Heihe and Khabarovsk etc may be permitted, to relieve the merchants’ hardship and bring benefit to the masses. We await your instructions with deepest gratitude.

Letter from the Maritime Customs, 11 May 1918. Zhong-e guanxi shiliao, Minguo jiunian zhi banian (1917-1919). E zhengbian yu yiban jiaoshe (1), pp. 367-368.

The language of the petition, replete with ethical terms, reveals an expansive conception of the merchants’ social role. Merchants (shang) ranked low in the Confucian social hierarchy. During the late-Qing reform movement, however, commercial strength became linked to national revival and merchants were expected to play a role in bolstering China’s economic status. At the same time, they drew upon Buddhist and Confucian ideas of virtue to justify economic goals – not unlike the Christian arguments employed by some American anti-bolsheviks during this period.

Changing circumstances in Siberia – most notably, the revolt of the Czech Legion – brought an end to the embargo in late-June. Nevertheless, as commerce suffered further shocks from the Russian Civil War, Chinese merchants continued to issue similar petitions. The language of protest only grew more strident as merchants came under direct attack from both Reds and Whites.